Anchor Steam, the fountainhead of America’s modern craft beer movement, was already in existence and Grossman had been impressed by what he had tried. He was at least aware that you could make a business out of brewing boldly flavored ales, but Fritz Maytag, who had turned that business acquisition around, was rich. What opportunity did Grossman have beyond running a homebrew shop?

Grossman and a fellow homebrewing buddy, Paul Camusi, had been pondering whether they could ever open a brewery. Then they visited the newly founded New Albion Brewery in Sonoma, California in 1978. This simple microbrewery—one of America’s first—made them realize that a shift from homebrewing to commercial brewing would be possible. What they didn’t realize at the time was that it would take much more money than they had, not to mention roughly two years of planning, setbacks, and exhausting work.

These days, the Brewers Association in America provides invaluable support to breweries. Brewers, too, generally share knowledge and help each other. Banks have become comfortable with loans to the craft beer industry; some even host booths at trade shows. Plenty of established business models exist for someone starting out. In 1980, however, when Grossman was reaching his breaking point in opening the brewery, there was little guiding light. Looking back now, what resources in particular does the brewing industry have today that Grossman wished he had then?

“It’s a little bit of a double-edged sword. I think that not having information available taught us to be resourceful, innovate and solve problems. We had to figure out how to brew consistent beer, we had to research a lot of issues on our own and I think that whole process was healthy. It gave us more respect for our art, as opposed to finding easy solutions to solve problems. I think problem solving is certainly a part of brewing. It’s also helpful in building your set of skills to run a business.”

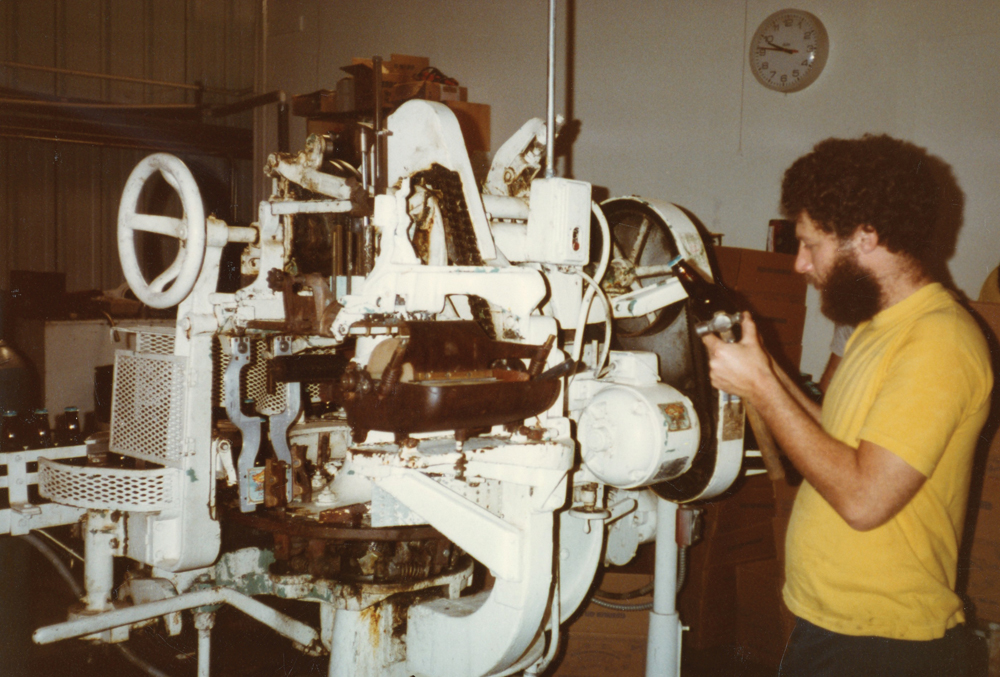

Problems, it seems, were all they had in the beginning and perhaps no start-up breweries now would hope for a similar experience. They burned through all of the initial $50,000 they pooled partly through the mistake of buying old, faulty equipment. They went back to family for more small loans. Grossman traveled to scrapyards, old dairy farms and defunct breweries to get the parts he needed to rig the brewery together. Even when they finally launched on November 15th, 1980, the challenges didn’t end. Their initial batch of flagship Pale Ale was a winner, but declined in quality with each batch thereafter. They discovered that yeast and a necessary equipment alteration were the culprits, but declined to sell the inferior beer.

Even today when asked about some of the biggest mistakes the brewery has made, Grossman comes back to this.

“We’ve dumped a lot of beer. We don’t like to do it and we don’t do it routinely, but we make the call and hopefully we’re right. If we’re concerned about some aspect that’s not meeting our expectations, I would rather err on the side of caution—let’s cut our losses rather than put out something we’re not proud of. That’s painful, particularly when it’s not that the beer is bad, but that it just isn’t the way you want it or that it doesn’t match another batch. We recently dumped a bunch of beer at the North Carolina facility. I’ve dumped beer here in Chico and I dumped beer at our original brewery. I’m not proud to do it, but I’d rather say I did it than kick myself later on and say I really wish I had done it.”

Sierra Nevada’s stringent commitment to quality has driven much of its success and Grossman notes that financially the brewery was essentially profitable from the beginning. It was still exhausting work, though. Grossman was sacrificing family time for long hours and no holidays. He recounts one episode of personally driving a pallet of beer in the flatbed of his old 1957 Chevy truck to one incredulous distributor in the San Francisco Bay Area.

While the hard work paid off and orders grew, so did headaches. Grossman found himself constantly tweaking and adding to the brewery over the next few years to increase capacity, resolutely refusing to contract brew for the short term. It’s a topic he has trouble hiding his distaste for, both in his book and in the interview.

This article was published in Japan Beer Times # () and is among the limited content available online. Order your copy through our online shop or download the digital version from the iTunes store to access the full contents of this issue.