Garrett Oliver is not simply one of the greatest brewers in the world of craft beer. He is widely respected in the culinary world for his knowledge about beer and food pairings. He is a popular lecturer about, and advocate for, craft beer, regularly speaking at events around the world. He is a successful author with several books in print, most notably The Oxford Companion to Beer. And when it comes to knowledge of beer history and traditional styles, few people know more. For that matter, he doesn’t just know beer history, he is changing it, helping to make craft beer the norm, not a niche.

I spoke with Garrett for about an hour recently―a generous hour for somebody as busy as him. Yet not nearly long enough for someone with as much to say as he has. Here is the best of that conversation.

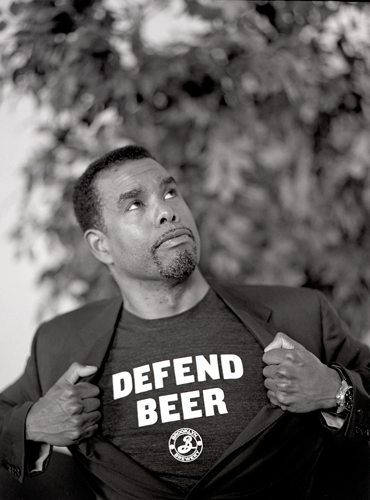

I remember when I met you at the Craft Brewers Conference 2012 in San Diego that you were wearing a shirt that said “Defend Beer.” Can you explain the philosophy behind that?

We needed a nice picture of the brewhouse production team. I asked for some black T-shirts that said Defend Beer with our logo on it, and then a whole bunch of broadswords. We had done an event with Marvel Comics who put us in touch with the producers of Game of Thrones. They, in turn, put us in touch with their sword makers. To this day, all of us in the brewing team have massive broadswords. And we have all these hilarious photos of ourselves in the brewery literally defending beer with swords.

Originally, there was a spate of T-shirts going around the city that said Defend Brooklyn with a picture of a Kalashnikov. I thought that what we’ve been doing all these years is defending beer as we know it from industrialization, from marginalization, from all the things that are trying to turn it back into a yellow, fizzy, uninteresting drink. Not only do we promote beer, but we also defend it.

Some members of the Brewers Association ignited a debate in America over “Craft vs. Crafty,” the notion being that some large, industrial makers are marketing beers that appear to be craft so as to take advantage of craft’s growing popularity. Where do you stand?

I’m of two minds. One mind, if you like, is the emotional one. We have been fighting this battle against the big brewers for many years. Many of the tactics they use are unfair in many cases and not allowed by law. They’ve done everything they could to limit our access to market in some cases. These are very emotional issues to small craft brewers who may have gotten a second mortgage on their homes and have really put their livelihoods on the line. Many deal with years of poverty to make it in craft beer. And then the industrial brewers show up dressed as you in a way. For me, it can be like walking into a room and there’s a guy that has your hat on, all your clothes on, and he says that he’s you. Of course, he’s not you. But the consumer can’t necessarily tell the difference. Particularly when you have beers that do not in any way announce their connection to an industrial brewer, that’s dishonest. They’ve figured out that the public doesn’t really like them any more, and so they’re trying to be something else. They say, ‘Let’s pretend to be something like Brooklyn Brewery or Stone Brewing.’

The intellectual side, however, is that these are massive corporations that have a responsibility to shareholders to try to grow their stock value. But there is no future in industrial brewing, period. They can’t make an argument to anyone that there is a future. So what did we expect them to do? Did we think they were just going to roll over and die? Of course not. These are very smart people. They’ve built companies that are over 100 years old. They are going to fight back. They are going to try to give people what they think they want: something that looks like craft beer. And as much as I would like the general public to be outraged by the industrial brewers, they’re not really paying that much attention. Craft brewers really should focus on what they’re doing: keeping their creativity, keeping their spirit, making the beers they want to make and bringing the public to those beers. Then everything else will sort itself out. The consumer will decide, but we’d prefer the consumer decide with actual information. That may or not happen so we have to continue to earn them every day.

I feel there’s a growing perception that there’s a gray area with the bigger craft breweries. Take Boston Brewery, for example; they’re a publicly traded company now and yet still considered a craft brewery by the Brewers Association. Lagunitas is opening another huge production facility in Asheville. And Brooklyn Brewery is no small company, either. At what point is it no longer craft brewing?

To me, it’s never really a matter of size. But I would say Boston Brewery is something like ten or fifteen times our size. AB InBev (makers of Budweiser, Corona, etc.) is 200 times their size. How are we not small? I do understand that our beers are everywhere. Japan was our first export market; we were there about a year after the brewery started in 1990. It’s natural that people think we’re big, but we have fewer than 100 employees. And I think that craft, at the end of the day, is in the heart of the brewer. Look at Sierra Nevada―they’re five times our size. But I don’t know any craft brewers that don’t look up to Ken Grossman. He’s a genius. And he has his hands in every single thing that happens in that brewery. Sierra Nevada is an expression of his vision of what a brewery should be. How could that not be craft? I think one way you can tell the difference between a brewery and a craft brewery is to ask, ‘Who’s the brew master?’ With a big brewery, nobody ever knows. The reason why is that what’s behind the big breweries is money, not a person, not a vision.

I’d like to go back to an earlier time in your brewery. You were there in the 1990s when it moved to a much larger facility in Brooklyn. That must have been both stressful and exciting.

Yes. I had known Steve Hindy and Tom Potter (the co-founders) for many years. We knew each other from the homebrewing scene of the 1980s and we’d always talked about working together some day. They were producing two beers, the Brooklyn Lager and Brooklyn Brown Ale, outside the city. They had no brewery in the city for me to work at so we just kept in touch. I was working at a place called Manhattan Brewing Company, where I had started in 1989. I was planning to purchase the company along with some British investors and then open up a series of brewpubs. Then Steve came to me and said, ‘We’d like you to come to Brooklyn Brewery and build a new brewery in Brooklyn.’ After many pints and lots of discussion, I went back to my British investors. The brewpub idea never happened, but they came with me to Brooklyn Brewery. We started to change things immediately. I reformulated Brooklyn Lager and Brooklyn Brown Ale. Then my first beer for the brewery was Black Chocolate Stout, and that was the winter of 1994.

Have you stuck with your reformulated Brooklyn Lager recipe since then?

Pretty much. There are always adjustments, more in the hop set than other things because hops change over time. One of the main things I did was change it from something like a steam beer―it was fermented at relatively warm temperatures with lager yeast―to something with deeper lager roots. With both that and the brown ale, I wanted to make them more like their traditional styles. I haven’t made any major changes since then which is interesting because Brooklyn Lager’s place in the market has changed radically. When it first came out, it was considered extreme. Most people had never seen an amber beer before, they had never had anything dry-hopped, they certainly hadn’t had anything with 30 IBUs. Those days are hard for some people to remember, but we built the market for craft beer in New York with this. These days Brooklyn Lager is popular among everyone from college students to retirees.

And yet it seems to be one of the few highly visible lagers in the craft beer scene in America. Why do you think there aren’t more lagers?

I think that the American craft beer scene obviously grows out of homebrewing. That’s where most of us came from. And in the early days, most of us had no control over temperature; therefore, we were unable to produce lagers. I’m going to guess that even today, maybe only 20% of homebrewers make lagers.

Where do you see the craft beer industry in another decade in terms of styles?

I think you’ll see things push out in a number of directions. There is certainly an interest in sessionability―beers that are very flavorful, but relatively low in alcohol. One of our brewers actually made a beer called Oishii (“delicious” in Japanese), which was a 3.5% saison based on our Sorachi Ace beer. You’re definitely going to see more interest in sour beers. You’ll see more interest in fermentations with wild yeast strains, namely Brettanomyces. When you see at the Great American Beer Festival that there are dozens of entries in the Berliner Weisse category, it tells you that there’s a possibility of sour beers becoming a part of the craft beer mainstream.

Do you brew any sour beers?

We have produced a number of sour beers, but we haven’t released them commercially. In any given year, we produce about 25 different beers that are available to the public. Then we have about 20 additional beers that we call ghost bottles. We have a relatively small production lot―maybe only 100 cases. Not enough to sell. These are beers that we bring to events and beer dinners. Among those, we’ve made a kriek, a Berliner weisse, a whole series of beers that we made with wild yeast that we got from a winery. They are sour and funky―definitely some of my favorite stuff that we make. One thing we hope to do by the end of the year is construct a barrel aging facility near the brewery where we could be housing up to 1500 barrels. Space in Brooklyn is very, very hard to get and is extremely expensive. The room right now that I can temperature control the beer we age in barrels is enough only for one commercial release: Black Ops. But we’ve made so many other ones and we want to allow people to have some of the other stuff we’ve been making for years.

How about projecting what the market will look like by 2020? Charlie Papazian, for example, has talked about gaining 10% market share.

I don’t know if we’re going to get there by 2020, but if you look at some place like Portland, Oregon where craft beer has 30 or 40% of the market, I think that is where craft beer is going to eventually end up. I just think it’s going to take longer than seven years. What you’re seeing in the U.S. is that rather than slowing, craft beer is expanding. And it’s doing it through the worst financial situation since the Great Depression. 2008 or 09 was the worst, but you saw craft beer taking off like a rocket. I think that’s one thing that made people realize that craft beer is here to stay.

There’s one thing that I think people need to understand about craft beer in the U.S. It’s a part of an overall food movement. It is not in any way, shape or form something that has happened by itself. When I was a kid, people ate lots of frozen food. Heavily processed supermarket food was the king of everything. Now you see, even in small towns, real cheese shops. There are supermarkets that will give you a whole aisle of olive oil. People are reclaiming the original American food culture. If you went back to 1900, what you would’ve seen in a place like New York was one of the most diverse, most fascinating food cultures in the world. Nowhere else would have come close to us. The same is true of the beer culture at the time. We had 48 breweries in Brooklyn! They made 10% of all the beer in the country. And these breweries produced everything. One specialized in weisse beer, another in porters, another in IPAs. You had people specializing in relatively new lager styles. Some were brewing indigenous American styles. If you went to Germany or Belgium or England, what you saw was the great beer cultures of those countries, but we had everything! We had been importing Bass since the mid 1800s. Guinness was already a staple. It’s important to understand that we didn’t come from nothing. We did once have a great food and beer culture because we had so many immigrants. That wouldn’t have been true in Rome or London or Paris. It was true in New York. That’s our heritage. We had everything because we had everybody, but we lost it. We gave everything away. What we have right now is not a trend, not a fad; it’s a return to normality.

It’s like barrel aging, which is a big trend among American craft brewers. People will say, ‘Wow, that’s great, you’re getting lots of cool ideas from wine people.’ I say, ‘Wait a minute, wine people?’ Beer has been in barrels for a thousand years. We stopped putting beer in oak barrels in the 1930s or 40s. The last barrels left the market in the 1950s. So in American beer, there has been a brief intermission when we weren’t using wood. Or look at the so-called champagne bottles that some of our beers come in with a cork and wire hood. First of all, that’s a beer bottle. Champagne was put in beer bottles and the technique for making champagne came from beer in the first place. What we have is a culture that wants to exalt wine and put things in wine terms, but this was all ours.

To return to food, when did your interest in food and pairing begin?

I was a cook first. It was my father’s big hobby. We hunted as well, for pheasant and quail with hunting dogs, sometimes on horseback. We’d come home and prepare them. My dad was a wonderful cook and taught me a lot of the basics. In college I was known as a good cook. When I fell in love with beer and started homebrewing, both food and beer were in my life, but they didn’t come together in my head until the late 1980s, when I began to host beer dinners at various restaurants. Then we started to do beer dinners at Manhattan Brewing Company. I started to see that people were delighted by what you could do with beer. This is where the book Brewmaster’s Table came from. I wanted people to realize that if they only paid a small amount of attention, the pleasure they get out of their meals could be exponentially increased. That was very simple in a way. It’s like jazz. It enriches your life, but there was probably a day when somebody played you your first Coltrane record. That moment, a small door opens up and on the other side of that door is literally a better life. All you have to do is walk through it. What I’ve tried to do all this time is to be one of the people that opens a door for you. That, on a day-to-day basis, is our job. We make beer, and I know it sounds grandiose, but we’re trying to give people something they like and provide a way to a better life.

How have your thoughts changed about food and beer in the ten years since you published that book?

I’ve done maybe a thousand beer dinners and tastings at this point. I’ve gotten to work with some of the best chefs in the world, which is a privilege. But I’m looking to dive deeper and deeper into it. We just hired a house chef at the brewery. We’re building a kitchen. Two of the other brewers and I cook regularly for audiences. We’ll make a five-course dinner. We’re not playing around either. We’re doing boneless quail stuffed with foie gras and truffles in a duck demi-glace from scratch in front of a crowd with full demonstration of technique. I take this stuff very seriously. While the beer dinner becomes a part of American craft beer culture, Brooklyn Brewery has always been cutting edge in that respect. It’s important to me that we remain a cutting edge brewery. What we’re doing you’ll see at no other brewery. And we’re building these things into a bigger part of who we are.

In 1998, you won the Russell Schehrer Award for Innovation and Excellence in Brewing. What do you think makes you innovative and cutting edge?

As far as I know, and as far as I’ve been told by journalists, we invented collaborative brewing. We hung our hat on that until 2001 or 02, when others started. Now it seems that everyone has collaborated with everyone else. We’ve done beers that mimic cocktails. One used scotch, ginger, honey and lemon. The beer was 60% peat-smoked malt, it had organic lemon juice, it had wildflower honey, and each 60-hectoliter batch had about 20 kilos of minced ginger steeped in it for five days and then strained out like dry hops. Draft Magazine called it one of the top-25 beers of 2011. We’ve always been a brewery that’s willing to take chances. A few months ago, I was in Brazil and we partnered with a small brewery called Wals. I wanted to execute this idea I had in my head so we cut down 700 kilos of sugarcane with machetes. I said we need to get a crusher at the brewery, and we’ll crush the sugarcane directly into the kettle, thus making about 15% of the wort from sugarcane juice. That’s a part of our spirit of innovation. We’re continually trying to reinvent our tradition. For me, it’s very important that as Brooklyn Brewery grows, we become more interesting, not less. Every day, every year, we go deeper. Market forces seem to say that if you’re getting bigger, you need more people to like you; therefore, you need to do things that are more commercially acceptable. We flip that idea around.

Of your many pairing dinners, have you ever done one in a Japanese restaurant?

I have done some with Japanese food, but never in a Japanese restaurant. Sushi has become a part of American food culture and has had a strong influence on many chefs, so I have worked with that. Right now, we are working on a beer for Ippudo that they serve on draft in New York, and we’re working toward possibly a series of beers for them, which I find really exciting because it takes me outside my realm of food knowledge. When I’m dealing with the broth at Ippudo, the flavors that are involved are extremely complex and not at all Western―it’s not just a pork broth. It takes them 24 hours just to make the stock. How my beer is going to interact with those flavors is very complex.

Do you have any expectations regarding your trip to Japan?

Last time I was in Japan, I asked my friend to take me to a place where I could get food and sake that I’d never have another chance to eat or drink. I was also blown away by Japan’s aesthetics―going to Isetan and seeing the food displays that made our best ones look like a corner grocery store. I’ve never seen anything as beautiful as that! And Tsukiji’s knife stores alone were amazing. This time, I’m interested in regional specialties in Japan. I can see at some point in the future doing something with Kiuchi Brewery (Hitchino Nest) like we did in Brazil that expresses locality. When I think about Japanese craft beer, I think that diversity is just now starting to happen, but the level of quality for the number of breweries is very high compared to other places that are in the same stages of their craft beer movement.

Regarding Brooklyn Brewery, within Japan, we’re kind of like a band where people are familiar with our great album, Brooklyn Lager, which we put out like 25 years ago. We’ve grown as artists and have put out forty albums since then. People still like that original hit album, but I don’t think there is any artist that wants to be known for just one thing when they have developed in all sort of different directions. What I’d like to do while in Japan is show people a little bit of the rest of us. Like musicians at a concert, maybe we’ll play three songs from that album, but we’re not going to play the whole thing. If people only look at Brooklyn Lager, they will not see us as we really are: as a highly innovative brewery doing a lot of fun stuff.

You’ve won quite a few awards and distinctions over the years. Are there any that you are particularly proud of?

Hmm, that’s a good question. The Brewmaster’s Table won the 2004 International Association of Culinary Professionals (IACP) Book Award. In 2012 The Oxford Companion to Beer won the André Simon Food and Drink Book Award, which is the top culinary book award in England. No beer book had won it since Michael Jackson won it. Those were obviously great moments. The Oxford Companion to Beer took four years out of my life and just about killed me. And it was the top selling book for Oxford in 2011. Then the 2003 Semper Ardens Award for Beer Culture in Denmark was big because it started all the things we have going on in Scandinavia now, including our opening a brewery in Stockholm in several months.

It’s nice to get awards, but two things have really stuck in my head. Yesterday, I got an e-mail from an African American woman who got named homebrewer of the year out in San Diego in a national competition. She said that I was her hero and that made my whole month. And I remember a woman coming up to me saying she was a schoolteacher and that she taught English. She said she wasn’t really interested in beer but started reading her husband’s Brewmaster’s Table because he was so interested in it. She said, ‘I just wanted to tell you that it is so very well written.’ Of all the nice things that people have said about my books, that was ten years ago and I still remember it. Then there are all the people who say, for example, ‘You don’t remember me, but years ago I was at one of your beer tastings and now I’ve fallen in love with craft beer, and I’ve been here and there, and I met my spouse at a beer event.’ It’s all that I can do not to burst into tears on the spot. People are having such a great time with that little moment you give them, with that door that you open. If you get a chance to do that on a continuous basis, then what else could you want? How many get the chance to make people that happy?

This article was published in Japan Beer Times # () and is among the limited content available online. Order your copy through our online shop or download the digital version from the iTunes store to access the full contents of this issue.