“Rasse-ra, rasse-ra!” shouts Be Easy founder Gareth Burns into the mic.

“Rasse rasse rasse-ra!” yell back the throngs of festival goers hopping in rhythm in tow behind the float. Aomori’s Nebuta Festival is in full swing and Burns isn’t content to be a spectator, or even a simple participant. He joins in the procession of dancers following the brightly lit Nebuta floats and makes his way to the front where the leaders of the chant belt it out ceaselessly. Dressed in his festival garb, Burns appeals to the mic holder to let him take the lead. Surprisingly, the man acquiesces with enthusiasm. And with that, Burns has taken over the stage at one of Japan’s most celebrated cultural festivals.

Those that know him surely aren’t surprised. In actuality, many do know him–or at least of him. He is a bit of a celebrity in Aomori Prefecture and people often stop him for a short conversation. More ardent fans ask him to pose for a photo with them. Burns appears in a popular weekly TV show called “Happy”, in which he visits places in the prefecture, chatting up people in the local Tsugaru dialect. Now in his fifth year on the show, he has gotten used to the attention.

It was one of his hobbies that led him to the current TV gig. Burns has been playing the Tsugaru shamisen (a traditional three stringed instrument that is plucked with a plectrum that resembles an ice scraper) for almost ten years. He had been entering competitions and regularly playing live in parks or local izakaya. Popular TV personality Hisamoto Masami visited his house in 2012 to do a show about him and he ended up on a national broadcast.

How did this lead him to opening his own brewery and restaurant? First, some background. Burns joined the US Air Force out of high school and was stationed at Misawa Air Force Base on the Pacific coast of Aomori. He arrived in the summer of 2005, but was deployed almost immediately to the Middle East that fall. Burns’ job was one of the more intense ones. He was a member of the bomb squad. He tells us, “I loved what we did. It came with a lot of responsibility and it was very rewarding. EOD (explosive ordnance disposal) guys don’t go out looking to harm people. We are stopping something from exploding and injuring people or damaging things. Being a member of the bomb squad became a big part of my foundation as a person. It helped change the way I approach things. It wasn’t just a physical learning experience as some people may associate the military with. It was an educational and emotional one as well. It has carried through with me in life and lets me take on new tasks or challenges from a different perspective. Things that may overwhelm some people seem approachable and doable to me.”

In the summer of 2007, after a little more than four years in the Air Force (two in Japan), he decided not to renew his commitment. He would have been deployed again and, in all likelihood, relocated to another country on his return. He wanted to experience Japan beyond life on the base so he became an English teacher. He had expected to stay for a year and then return to the US to put his military experience to use at the FBI or a similar government organization, but he took interest in the Tsugaru shamisen and that altered his course significantly. If he went home, he didn’t think he would find an adequate teacher and the effort he had put into studying the instrument would have been wasted. Returning to the States was put off one more year, then another, and another, until Hirosaki City became “home”. After frustrating experiences with some of the larger Eikaiwa (English language) companies, he opened his own English school six years ago in town so he could be his own boss.

Of all places, Hirosaki was where he had his first craft beer, Hitachino Nest’s Weizen, at a small Italian restaurant. Burns relates, “Obviously it wasn’t the same as the beers sold at izakayas and establishments offering nomihodai (all-you-can-drink beer). I thought to myself, why is this such a restricted commodity? Why isn’t this kind of beer served all over?” His interest deepened and he did some hunting online, eventually finding Phred Kaufman’s Ezo Beer site (based out of Sapporo). He actually sent Kaufman messages and often ordered a few random bottles or cans for delivery. Burns laughs, “At that time I was pretty naive. I didn’t realize people were buying cases and cases from him.” Kaufman was kind enough to send the the individual bottles anyway.

Soon interest evolved into more of a fixation. He went around Hirosaki trying to convince bar owners that they should sell craft beer, but he was always met with, “Nah, nobody here wants to drink that stuff.” So he began to make frequent excursions to Tokyo specifically for the purpose of drinking craft beer. It became routine to stop by one of Tokyo’s pioneering craft beer pubs, Popeye, and over time Burns became friends with owner Aoki Tatsuo. After some homebrewing experience with friends on base in Misawa, he started thinking that if no one in Hirosaki was going to sell craft beer, maybe he should just open up his own brewery.

He started to look into how to go about building a brewery without spending an exorbitant amount of cash. He discussed this with Aoki, who had opened his own brewery (Strange Brewing, see JBT issue #21), and Aoki connected him with Outsider Brewing’s Niwa Satoshi (see JBT issue #25), a man that has guided many in the industry in Japan. Niwa introduced Burns to affordable suppliers in China for sourcing equipment and gave him some pointers. Assembling everything was going to be a do-it-yourself job. Burns had learned the inner components of nuclear weapons in the military so wiring the control box to fire some valves or a pump in a brewery wasn’t a daunting task.

His next mission was finding a suitable building. He approached the city for support in bringing a hometown brewery to Hirosaki, but they had no interest in the project. Whenever he found a suitable place, he ran up against inexplicable regulations that disallowed brewing beer on the premises. “I wasn’t sure if they were just giving me the runaround or they simply didn’t know what to do since there was no brewery anywhere in the area,” says Burns.

A friend that was a real estate agent finally found a place that could both physically house the brewery and satisfy all the legal requirements. The two-story structure already had a thick concrete base and a framework of steel beams, and the first floor had a high ceiling, so only a small investment in alterations was required. It was a perfect setup for a brewery with a taproom on the second floor. Financing became the next hurdle. The banks he went to were as unhelpful as the city office had been. His loan applications were rejected on multiple occasions without much explanation, even when he pressed them. Though married since 2011, he insisted on doing all the paperwork himself instead of relying on his wife, Yukako. He wrote up the business plan and made frequent trips to the bank to present it to them–and get turned away frustrated.

His real estate agent pal stepped in again and introduced him to another bank that he thought might be more receptive. They listened carefully as Burns explained what craft beer was, and how he thought he could make a brewery and build a brand in Aomori much cheaper than in Tokyo or bigger cities. He detailed how he could distribute his beer and market it as a product of Aomori. They listened, but weren’t completely ready to commit at first. Then he did what any lover of fine brew would do: he took them out for drinks and a lesson in craft beer.

He set up a blind tasting with a bottle of his homebrew, a bottle of Sierra Nevada Pale Ale, a Japanese craft brewery’s pale ale and an industrial lager from one of Japan’s big four. All agreed that the industrial lager (without knowing what it was) was their least favorite and the other three were all quite good. He then revealed that two were from well-known craft breweries and the other was his own. Taken completely by surprise, they bought into his plan. From then on they were intent on making the venture work and even did most of the paperwork for him! He took a loan out in his name and poured all of his savings into the business. He still had income from his English school and as money came in, he threw it bit by bit into the brewery.

The large majority of work at the brewery was done by Burns and his staff or friends. When something perplexed him, the ever-reliable Niwa would send him a sketch to help him figure things out. Burns says the first brewday was a “16-hour disaster”, but when it fermented out he had a good product to sell. As soon as it was kegged, Aoki was customer number one.

That first beer (a pale ale) was originally going to have a Tsugaru dialect name (the plan for many of the brews), but on returning home from that miserable day of brewing, Burns realized it was his mother’s birthday. He couldn’t name the beer he coincidentally brewed on that day without her in mind, hence it became Debbie’s Pale Ale, a Be Easy standard. His dog, Ray, was also granted his own beer in Ray’s Milk Stout. Wife Yukako patiently awaits her turn for a beer to be named in her honor and daughter, Ellie, will probably make a case for herself when she can make complete sentences.

The local dialect dominates the other beer names.The Nda Pale Ale (meaning “But of course” or “That’s right”) is a relatively hoppy pale with a fruity aroma and a decent kick (6.2% ABV). Nottsudo IPA (translated as “a whole lot of”–referring to the amount hops and oat malt) is a strong 7.5% ABV beer in the realm of a New England IPA. Adohadari (one more round!) Rye Ale (6.3% ABV) touts a substantial rye backbone balanced nicely with hop bitterness. Keyagu (meaning “friend”) is the nomenclature used with collaboration beers, two of which Be Easy has done with bars (Craftbeer Hoppers in Morioka and Boku to Inu in Osaka). There are more interesting names, and deciphering them will require the help of an Aomori native.

While the brewery was being assembled, the team was also getting the taproom ready. All of October 2016 his staff was basically volunteering to get things up and running. At that point, Burns was out of cash and unable to pay anyone until a revenue stream was established, but everyone pulled together to finish construction, order equipment for the taproom and develop a menu. In November the taproom opened for business.

The original plan was to be distributing most of the beer elsewhere in Japan until people in Aomori caught on and visited his establishment. The reality turned out to be the complete opposite. It was difficult at first to sell kegs by email and sales were initially slow. Conversely, there were a lot of people that had been waiting for a craft beer bar in town–far more than Burns had anticipated. The bar was busy from day one and soon after opening there were people taking the 50-minute train ride from Aomori City to Hirosaki for the experience. The bar continued to be much busier than expected and little by little keg sales increased as well. In late spring of this year Be Easy had to add two more fermenters (bringing the total to four) to keep up with demand. As it turns out, doubling in size wasn’t enough and two more vessels are planned for early 2018.

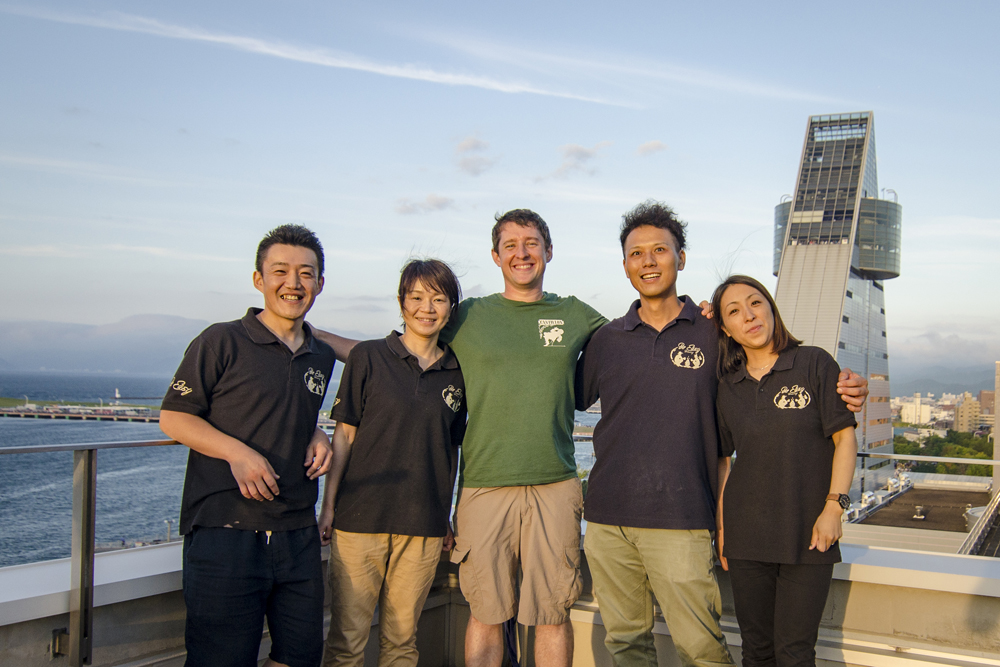

Burns attributes much of this success to his team. None of his four staff members had ever worked in a brewery or in the beer business. He chose them specifically because of their character and the fact that they believed in him. He involves all of his staff in decision making and shares his ideas and vision with them. In return, he expects them to be fully honest if they disagree with him. Burns heaps praise on them saying, “I won the staff lottery. No member of my team is replaceable.”

One of the most recent ideas he presented to them was the purchase of a plot of farmland. At first everyone was skeptical since not one of them had any farming experience. With everything going well at the brewery and restaurant, why would he want to take on more? Burns explains his reasoning, “I’m not an extreme environmentalist, but we’ve gotten so used to being able to eat, say, garlic from Mie Prefecture whenever we want. When you really think about what it takes to get that garlic to your house, it’s ridiculous. The idea of transporting stuff all over the place is so wasteful, but no one really considers it. That shouldn’t be OK. I can’t stop that, but what we can do here is grow as much of what we can for our restaurant.”

When he was talking to public officials and neighbors about buying farmland, Burns got the same negative response as when he brought up opening a brewery. “They said ‘Bad idea, Gareth. You don’t understand farming. You don’t know how hard it is.’ I wasn’t saying it was easy. I just believed we could do it.” He explained to his staff that they were going to lower their carbon footprint and they could take pride in the fact that some of the food they could serve would go farm-to-table by their very hands.

Another driving force behind the farm was disposal of spent grain. Oddly, no local farmers wanted to take it off his hands, even for free. They told him it wouldn’t make a difference using it to grow their crops. For a time he was dumping it in his backyard and noticed that the grass around it was growing much faster. He dumped it in a different area. “Monster grass–science experiment complete,” laughs Burns. He decided to move forward with starting the farm and got a deal on some land that no one was really interested in. He invested about ¥10,000 (less than $100) in some seeds and tools, lined the garden bed with spent grain, and just like his grass, the vegetables took off. Now they have more organically-grown vegetables than they can use at the restaurant, and the staff or friends get to take some home. He has moved some hops that he started growing in his backyard to the farm and expects to be using them in his brews soon.

While Burns continues to be an extremely busy person, he is now able to look back on what he has accomplished and breathe a little easier. At the same time he was building the brewery and taproom, he had his English school to continue running, a weekly TV show and a newborn daughter. It was stressful and draining. Burns recalls, “There were two or three times when I thought I should’ve never done this. This is the worst idea I’ve ever had. I can’t do it anymore. For a year and a half it was endless. It was overwhelming. But little by little things came together.” Now if a single thing goes wrong in the brewery, he is confident in his ability to troubleshoot because he put it all together himself. His confidence has rubbed off on his staff, too. They are empowered and the can-do attitude has become infectious.

Now armed with his Cicerone Level 2 certification, which he received in June, Burns is a man on a mission. Telling him he can’t succeed just adds fuel to his fire. As a member of the bomb squad, failure wasn’t an option. If he could perform under the exceptional stress of that job, then he could appear on TV without being nervous or start a brewery when people called him a fool.

Much as he took over at the Nebuta festival on that August night, Burns is taking over the craft beer scene in Aomori. Be Easy is also becoming a more recognized name in the vibrant craft beer markets of Kanto, Kansai and beyond. The doubters are quickly fading away as he has continually proven them wrong each time. Count this author among the believers.

This article was published in Japan Beer Times # () and is among the limited content available online. Order your copy through our online shop or download the digital version from the iTunes store to access the full contents of this issue.