Text and photos by Professor Mark Meli

Yeast is the soul of beer. It is this invisible agent, unknown to humans until the mid-19th century, which takes sweet, simple wort and ferments it into something beautiful. Yeast produces alcohol, the muscle of beer, and CO2, its spirit. Yet yeast never seems to get its fair share of attention. Until the release of Louis Pasteur’s Etudes sur le Vin in 1866 and, more importantly, Etudes sur la Bière in 1876, people actually had no idea what caused fermentation. Before Pasteur, people thought that alcohol was somehow spontaneously generated in wort or fruit juice, and this led many to attribute these spirit-lifting drinks to the benevolent work of a deity. That is surely one reason why Japanese sake is so often made as an offering at Shinto shrines, and why no Catholic mass is complete without a sip of wine, symbolizing the blood of Christ.

Before Pasteur turned his microscope on beer and gave brewers a clue to how to control yeast, and thus manage the flavors of fermentation, all yeast was wild yeast. All beer was naturally fermented by the yeast that was around: ambient in the brewery, or, if the wort wasn’t boiled, on the husks of grain. When a batch turned out to be particularly delicious, some of that beer was poured into the next batch, where it would somehow pass on its magic, resulting in a similar flavor again. Breweries, without knowing, developed house strains of yeast, which they started to investigate scientifically, and even buy and sell, after reading Pasteur’s work.

Today, things are so much simpler. Now almost all craft brewers use yeast which comes in one of two forms, either a small packet of powder, or a vial of cloudy liquid. These bear brand names like Wyeast, Safbrew, or White Labs, and official numbers. WLP090, for example, is “White Labs San Diego Super Strain,” a popular yeast for brewing IPAs. These over-the-counter yeast strains have been isolated from well-known beers, then purified and grown in laboratories. Being able to buy yeast so easily, and with it reproduce (with the right talent) nearly the exact flavors of the German Hefeweizen, Wallonian Saison, or English Ale you aim for, has certainly been a huge step in bringing craft beer to the masses. Yet one might argue that it has led to a kind of uniformity of flavor as well. Japanese craft beers are generally made with the same yeasts as American, Australian, and Canadian craft beers, which are made from strains which were developed in the British Isles, Belgium, Germany or Bohemia.

Shift focus to Talmary, in Chizu, Tottori Prefecture. This is currently the only brewery in Japan which ferments all of its beer with wild yeast. The concept behind Talmary came from owner Watanabe Itaru (the “Tal” in Talmary—“mary” is his wife, Mariko). Watanabe is a baker, who has long baked breads using natural yeasts. This passion led him to want to try brewing beer in the same way, which would also conveniently provide him with a stock of yeast for baking. At the previous location of Talmary, in Maniwa of Okayama Prefecture, Watanabe hired Miura Hiroshi, who also loved natural yeast breads, but was hoping to become a brewer. In preparation for his future task, Miura spent some time training at Outsider Brewing under the tutelage of the man first known in Japan for wild yeast beers, Niwa Satoshi (try his Outsider Tripel, or Iwate Kura Shizen Hakkō Beer).

It was Miura who isolated the two strains of yeast that are used to ferment Talmary Beer. First came the “Maniwa Yeast,” which was procured from a container of wort that Miura left out overnight in a forest in Maniwa. This is a gentle strain which leaves behind a bit of residual sweetness and a pleasant fruity character. After Talmary was re-located in Chizu, Miura developed his second strain, which he calls “Kaki-nashi-reizun kōbo,” or “Persimmon-pear-raisin yeast.” This was first collected from pieces of persimmon and pear which were left out in the forest behind the brewery. When this yeast was found to quit mid-way through the fermentation, some fresh raisins were added to it, and it was left to develop a bit more. The resulting strain is indeed quite powerful, producing high attenuation and a dry, slightly tart, peppery flavor. In my opinion, the raisins have also imparted something of a champagne-like character to the yeast. It is fun to try to guess which strain has been used in each Talmary beer.

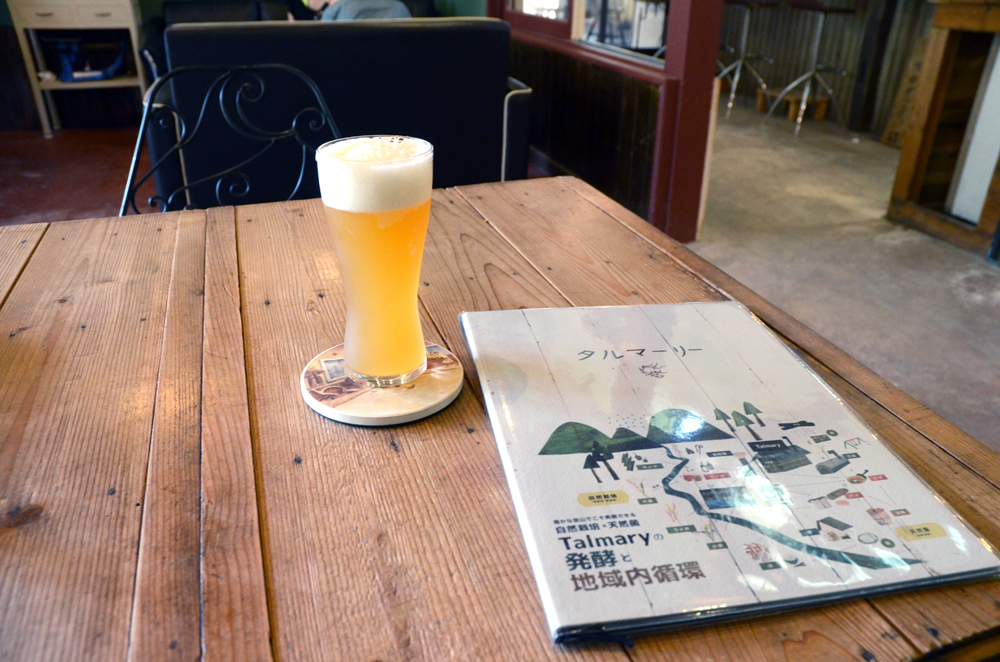

In June, 2015 Talmary relocated to an abandoned nursery school in Chizu, on Tottori’s southern border with Okayama. It is in a narrow valley flanked by steep mountains, wooded mostly with sugi and hinoki trees (Japanese cedar and cypress trees). The reason for choosing the site was not just the view and the variety of rooms it provided; the main draw was the well it sits upon. Talmary beer and bread are made using water from this well, which you can also drink in the café. It is soft, fresh, and cold, and was quite delicious on the 36°C August day when I visited. This former nursery school now holds a milling room, bakery, kitchen with pizza oven, brewery, patio, and several rooms for eating and drinking. The café and shop specialize in homemade bread and pizza as well as the local vegetables and meats that are plentiful in Chizu. I had a wild boar hamburger served on sourdough bread and garnished with locally grown veggies. It was perfect with the Chamomile Saison. The café is less than 10 minutes’ walk from JR Nagi Station. Although this is on a line with less-than-frequent trains, it can be reached in less than 3 hours from Osaka station. Check their website for hours before visiting.

Part of the mission statement of Talmary is to use local ingredients as much as possible. Besides their well water and wild yeast, up until now they have used regionally-grown barley, wheat, yuzu, orange peel, honey, and apples in their beer (which by law is happōshu). While I visited, we also spoke of the hops they were growing, and their intention to malt locally-grown barley in the future as well. It will be fascinating to see how these plans develop.

I want to avoid imparting any wrong ideas about Talmary beers due to my stress on their wild yeast. First of all, these are not sour or lambic-type beers. The strains as developed contain no Brettanomyces or lactic acid bacteria. Thus while they do tend to be slightly tart and complex, they have no “horse blanket” funkiness or vinegar flavors. Secondly, you must not imagine that, with all the emphasis on yeast, Miura is shy in using hops. He is not. Thus many of his beers feature fabulous hop aromas and flavors, and he seems fond of looking for just the right blend of New and Old World hops to get the job done.

The wild yeast strains that Miura uses do create something like a Belgian quality in his beers, probably closest to a Wallonian farmhouse saison. This must be why Belgian-influenced styles have so far formed the majority of his brews. Pale Saison is now the only year-round beer, with a fruity, spicy nose full of citrus hops and a tart, dry flavor with a peppery finish. The light tartness from the yeast goes very well with the citrusy hops. The Chamomile Saison is a completely different beer, however (they use different yeast strains), with hints of stone fruit and a bit more sweetness—even a touch of honey. Big grapefruit and lemon aromas pair very well with the light herbal character of the chamomile. This is a superb beer, a great example of how to use herbs to add interest to a beer without covering up its original character.

Hop White is a beer I got to sample straight from the tank. It is basically a Belgian witbier, but without coriander or orange peel. The spicy flavors come from the yeast and Zanthoxylum piperitum (sanshō) fruits, and the citrus from a complex blend of Galaxy, Hallertau Blanc, and Mandarina Bavaria hops. This beer was super dry and nicely tart, perfect on a hot summer day. Galaxy hops are the showcase of another beer, Galactic Pale, wherein the grapefruit and lemon notes of the hops blend perfectly with the tart, mineral character of the fermentation to create something like a new-wave hoppy Belgian pale ale.

I was also impressed by Smoke Stout, which uses barley roasted in the bread oven; Spring Blond, which had notes of tropical fruits and peaches; and Yuzu Dubbel, a fascinating beer of tart yuzu meshed with spicy chocolate malt flavors.

At this point, most Talmary beer is consumed in and around Chizu. Some is sent to friends’ restaurants in Tokyo and other parts of Japan, and it has been seen at a few craft beer festivals. With just four 500-liter fermentation tanks and a 250-liter brew kettle, there is not much beer left over. Luckily for me, a few extra kegs have found their way into Kansai craft beer bars recently, where I’m able to sample them. As usual, though, I thought them best when fresh at the brewery.

It is great to see such a unique approach to brewing arise in the mountains of Tottori. Even more inspiring is the fact that in such a short time, in such a small brewery, and using only wild yeast, such lovely beers are already consistently being made. I can’t wait to see what comes next.

This article was published in Japan Beer Times # () and is among the limited content available online. Order your copy through our online shop or download the digital version from the iTunes store to access the full contents of this issue.